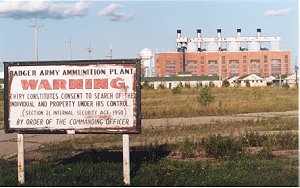

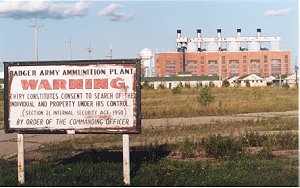

About Badger Army Ammunition Plant (BAAP)

Badger Army Ammunition Plant

- Profound Environmental Damage

- Elevated Cancer Rates

- Cleanup Plans Abandoned

- Conversion to Peace

- Ecological Restoration

- Wisconsin River Watershed

- Regulation of Conventional and Chemical Munitions

- Cleanup Authority at BAAP

- Badger Army Ammunition Plant

Badger Army Ammunition Plant Background Narratives

Profound Environmental Damage

- Industrial Operations at Badger Army Ammunition Plant

- Environmental Regulations

- Base Closure

- Biological Resources

- Bird Inventories

- Ho-Chunk Nation

- State and Federal Agencies

Profound Environmental Damage

Environmental cleanup of the 7,400-acre Badger Army Ammunition Plant is expected to exceed $250 million. Of the 40 contaminated military sites in Wisconsin, the Defense Environmental Restoration Account cites Badger as the most contaminated; 32 areas within the plant are polluted with high levels of solvents, toxic metals and explosive wastes. Groundwater beneath the plant is contaminated with cancer-causing chemicals, including carbon tetrachloride, trichloroethylene and dinitrotoluenes. An area known as the Propellant Burning Grounds is the source of a three-mile long plume of contaminated groundwater that has migrated offsite, polluting private drinking water wells in its path and dumping into the Wisconsin River.

Elevated Cancer Rates

In 1990, in response to community concerns about these exposures, the Wisconsin Division of Health conducted a health survey. The study concluded that communities near the Badger plant have a significantly higher incidence of cancer deaths; the incidence of female non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and male ureter /kidney cancer deaths were found to be 50% higher than the balance of the State. Despite these alarming findings, the State refused to take any subsequent action. In 1995, the Division of Health finally responded to pressure from CSWAB and agreed to reopen the community health study.

On October 26, 1998, CSWAB submitted written comment on a draft Public Health Assessment published the previous month by the Wisconsin Division of Health. CSWAB concluded “there was entirely inadequate contact with our community – the population being studied.” Prior to September 1998, no press releases were published, no public informational meetings were held, and no interviews were conducted with stakeholders. The result is an absence of even the most basic understanding of local concerns and conditions.

Despite several requests by CSWAB, virtually no resources were devoted to interviewing residents as to current health problems and concerns that they associate with their proximity to the Badger Army Ammunition Plant and their exposure to air, fugitive dust, emissions, and surface soils; associated and multiple routes of exposure were also not assessed. Assessment of risk from current, pending, and anticipated cleanup activities was also noticeably absent. CSWAB also determined the WDOH has concentrated on the wrong type of illnesses, e.g. focusing on death studies when many health problems and community concerns have been nonlethal, such as respiratory illnesses or reproductive problems.

CSWAB has appealed directly to ATSDR’s Board of Scientific Counselors Subcommittee which met recently in Washington, DC to discuss the lack of adequate community participation in this and similar health assessments across the nation. The Wisconsin Department of Health conducted the assessment under a cooperative agreement with ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry), the federal health agency responsible for final approval of the study.

Cleanup Plans Abandoned

Contrary to an enforceable agreement with the State of Wisconsin, the Army now proposes to abandon and severely reduce cleanup of two priority areas within the plant. One of these areas, the Settling Ponds and Spoils Disposal area — a series of lagoons that run the length of the 7,000 acre facility — is contaminated with high levels of lead and carcinogenic dinitrotoluenes. Instead of a $60 million cleanup approved by both the State of Wisconsin and the USEPA, the Army proposes fencing and long-term monitoring of groundwater.

If the military is granted the compliance exemptions they seek, huge expanses of land at Badger will be fenced off as unsuitable for development, human habitation, or even wildlife habitat. Groundwater resources and nearby drinking water wells will be at increased risk as pollutants migrate to groundwater.

Many community members do not have the resources to continually test their drinking water wells for contaminants associated with Badger, violating federally-mandated environmental justice principles to provide low-income people with equal protection of human health and their environment. Moreover, any exemptions granted at Badger, will certainly spur demands from other contaminated military and civilian sites for similar concessions.

Conversion to Peace

Maintenance of the Badger plant — although not in production since the 1970’s — costs in excess of $17 million per year. In 1991, by contrast, only $3 million was allocated for environmental studies. Built in 1942 in response to World War II, the production facilities at the Badger plant are obsolete and would require over $119 million in upgrades to meet current state and federal environmental standards. In addition to these extraordinary fiscal costs, environmental damage continues to plague the facility — since 1975, there have been over 56 chemical spills and incidents. Moreover, there is no national strategic need for maintaining the Badger plant. A February 20, 1997 Government Accounting Office report concludes BAAP and three other military plants could be eliminated “because alternative sources exist…to provide the capabilities these plants provide.”

Ecological Restoration

The expected decommissioning of the Badger Army Ammunition Plant represents one of the greatest opportunities for large-scale conservation in southern Wisconsin. In the coming year, CSWAB’s work will focus primarily on influencing the future use of the Badger Army Ammunition Plant.

When the first European visitors came to this land they encountered a mosaic of tallgrass prairie, open woodland and scattered mixed forest in the Baraboo Hills. The large plain sandwiched between the Baraboo Hills and the Wisconsin River was known as the Sauk Prairie, a 14,000-acre expanse of tall- and short-grass prairie. The closing of the Badger Army Ammunition Plant presents a rare opportunity to protect a piece of our prairie heritage that has almost been lost in Wisconsin and the Midwest.

At the same time, Olin Corporation, an international chemical company responsible for such environmental catastrophes as New York’s Love Canal, is actively lobbying for conversion of Badger to a monstrous industrial complex including varnish, paint and lacquer manufacturers, ethanol and cosmetics industries, and nitrogenous fertilizer plants. The proposed industrial park will be larger than all of Sauk County’s existing industrial parks combined – more than 600 acres.

Accelerated, scattered rural development in the Hills will increase as people move into the area for jobs at the newly redeveloped plant. Scattered rural development poses the largest threat to the unbroken forest that covers the Baraboo Hills. These hills are nationally recognized for their outstanding geology and diverse ecological resources; they include some 40,000 acres of mature second-growth forest that is home to 23 species considered threatened or endangered.

The Nature Conservancy, under a federal contract with the Department of Defense, conducted a biological inventory at Badger in 1993 and found a wide variety of natural community or habitat types, including remnants of prairie and savanna. Many rare or uncommon plant, animal, and insect species were also found, including a large number of grassland bird species of special concern in Wisconsin.

The Badger property presents the unusual opportunity to manage a continuum of prairie, savanna, and woodland vegetation stretching from the Badger prairie into the Baraboo Bluffs. Protecting this land would maintain an important part of Southern Wisconsin’s history and unique natural resources.

Two nearby decommissioned military facilities–Joliet Arsenal and the Savanna Army Depot (both in northern Illinois)– serve as models for our vision for the future of the Badger plant as these former military facilities have been closed and ecological restoration is planned for the sites. At the former Joliet Arsenal (near Joliet, Illinois), a 19,000-acre restored prairie –the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie–has been planned for the 23,500-acre facility. Strong, effective grassroots organizing made these successes possible.

The community must come together to develop a vision — a vision that reflects the needs and priorities of the community. A vision that is sensitive to the economic needs of the community, that is considerate of adjacent lands and resources and promotes protection and preservation of indigenous plants and animals. A vision that will improve and enhance the quality of life for ourselves and our children and will nurture and protect our natural resources.

Wisconsin River Watershed

Surface water and groundwater resources in and around the Badger Army Ammunition Plant, located in the Wisconsin River watershed, must be protected. Of special interest are 13 ponds within the site; some of the ponds are formed in borrow pits or are old farm ponds. Others are natural kettle ponds. Previous biological surveys have indicated these surface water resources provide valuable habitat for unique fauna, particularly aquatic beetles and amphibians. The largest water body on the site is the 7-acre Ballistics Pond, which drains about 1000 acres north of the plant and 450 acres of plant property.

Groundwater at Badger is hydrologically connected to the nearby Wisconsin River. Groundwater contaminants — tricholorethylene, carbon tetrachloride and chloroform — emanating from the Badger plant have migrated several miles offsite and have reached the Wisconsin River. At the same time, proposed reindustrialization will increase direct industrial and sanitary wastewater discharges, further reducing already depleted available oxygen levels in the river.

Potential contaminants in the discharge, which will exceed 4,000 gallons per minute, threaten the river ecology. The Wisconsin River together with its associated tributaries and wetlands provides drinking water, supports and sustains wildlife, provides habitat for fish and aquatic species (including the Mississippi paddlefish and the American Bald Eagle), fulfills a wide range of recreational needs, and is an invaluable and irreplaceable natural resource.

Regulation of Conventional and Chemical Munitions

The environmental legacy of the federal government’s mission-oriented activities is felt in communities throughout the country. Environmental cleanup of the 24,000 sites on federal facilities in the United States may ultimately cost as much as $400 billion and will extend well into the next century. Congress, realizing that external oversight of military activities was essential to protect human health and the environment from further damage, passed the 1992 Federal Facilities Compliance Act. This federal law directed the USEPA to promulgate rules intended to force facilities like Wisconsin’s Badger Army Ammunition Plant to comply with existing waste disposal laws.

The proposed Military Munitions rule, however, falls far short of Congressional intent and effectively exempts most military activities from compliance. Unless challenged, many military activities, including open burning and detonation of munitions, will remain unregulated. Open burning and detonation constitutes an uncontrolled release of poisonous nitric oxide gases and respirable metals-contaminated particles (lead, cadmium and chromium) which are toxic to humans and bioaccumulative in the environment. Exposure to dinitrotoluenes (a chemical found in propellants) in open burning emissions place soldiers, workers and nearby residents at increased risk for liver, kidney and breast cancers.

Moreover, virtually all response actions in the proposed Military Munitions Rule are triggered by risk as defined by the military, compounding existing health and environmental risks to the very communities we should be protecting. Communities and tribes, particularly those that are not well organized, will be placed at greatest risk as this rule denies them protection afforded by regulatory compliance, denies a legal appeals process, denies comparable access to information and denies participation in the decision-making process.

CSWAB, together with the national Military Toxic Project network, plays a critical role in fighting for a strong federal military munitions rule that will protect human health and the environment by providing for the safe storage, handling, testing, and disposal of conventional and chemicals munitions.

Infield Conditions Report Approval, September 14, 1987, and subsequent modification approvals.

This document is based on State and Federal hazardous waste laws. It addresses each of the significant sites that have been identified at Badger and details what specific work must be done and what standards must be met.

State Statute 292.11, The Spills Law.

This statute requires persons responsible for releases of hazardous substances to the environment to remediate such releases to the

appropriate standards.

Natural Resources Administrative Code 700.

These are the environmental clean-up rules. They define responsibilities for clean-up and provide for how standards for clean-up are to be established.

Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA), 42 U.S.C. 9601, et seq. and Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) 42 U.S.C. 6901, et seq.

These are the federal laws that provide the basis for Wisconsin

environmental protection laws and rules. Wisconsin is a fully authorized state relative to environmental protection laws. In other words, the Department of Natural Resources has demonstrated to the United States Environmental Protection Agency that the programs we have in place meet

or exceed the federal requirements. Therefore, we have full authority to implement our environmental protection programs backed by the federal legislation.

Prepared by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, October 2001.

Industrial Operations at Badger Army Ammunition Plant

The land required for Badger Ordnance Works was procured by the government on March 1, 1942 and construction was started midyear in 1942. A letter of intent was signed with Hercules Powder Company on November 10, 1941, authorizing it to initiate surveys and design Wisconsin plant. The Hercules Powder Company was selected because it had successfully completed the construction of the Radford Ordnance Works near Radford, Virginia, and the Badger plant was to be a duplicate of the smokeless facilities at Radford. The plant was built by the Mason and Hanger Company of New York City.

BAAP production started in January 1943, and continued until September 1945, when the plant was placed on a standby status. During the operational period, BAAP employed 7,500 people and manufactured 271 million pounds of single and double base propellant.

On December 15, 1945, BAAP was declared surplus by the U.S. Government. In October 1946, the rocket facilities were withdrawn from surplus and placed in standby status. From 1945 to 1950, various portions of BAAP were in surplus, standby, and caretaker status and maintained by a small force of government employees. Over 4,189 acres were disposed of during this time, of which 2.2 acres went to the Kingston Cemetery Association; 2,264 to the Farm Credit Administration; and 1,922 to the War Assets Administration, bringing the total acreage available for BAAP operations to 6,380 acres.

During the early 1950s as a result of the plant reactivation for the Korean conflict, 1,173 acres were reacquired, bringing the total acreage to 7,553 acres. Rehabilitation of BAAP by the Fegles Construction Company was completed in 1955 and the Liberty Powder Defense Corporation was contracted to operate BAAP. Through merger, the company today is known as the Olin Corporation. Total production during this period (1951 to 1957) was approximately 286 million pounds of single and double base propellant and employment peaked at 5,022 employees.

On March 1, 1958, BAAP was placed in inactive status. During this period, the land directly across from the main entrance on Route 12 was declared surplus and the acreage of BAAP was reduced to 7,417 acres. The plant was reactivated effective December 23, 1965, with rehabilitation by Olin Corporation and various subcontractors. The propellants manufactured included ball propellant, smokeless propellant, and rocket propellant. Total production for this period was approximately 445 million pounds of single and double base propellant including 95 million pounds of ball propellant; 64 million pounds of rocket propellant; and 282 million pounds of smokeless powder. The plant at peak of production employed 5,390 people during this period.

On March 24, 1975, the Department of Defense ordered production operations at BAAP to cease upon completion of current orders and placed the installation in a standby status. This was the third such closure in the 50-year history of BAAP. Decontamination of facilities to the XXX condition was accomplished by the operating contractor, Olin Corporation, immediately upon completion of production operations and was completed in March 1977.

Environmental Regulations

The U.S. Army and Olin Corporation have been jointly issued a RCRA Permit by the U.S. EPA and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). The State portion allows the facility to store up to 10,000 gallons of hazardous waste in containers at the facility.

At the time of the permit issuance, the State of Wisconsin had not received authority to administer the Hazardous and Solid Waste Amendments (HSWA) to the Solid Waste Disposal Act. HSWA provide authority to U.S. EPA to establish additional permitting requirements for hazardous waste management facilities beyond the scope of existing regulations, if necessary to protect human health and the environment. The State has been subsequently authorized to administer individual provisions of HSWA. However, because the State had not received authorization to address the HSWA requirements by the date on which the RCRA Permit was originally issued to the U.S. Army (as owner) and Olin Corporation (as operator), the U.S. EPA issued its own permit, jointly with the State permit, addressing the HSWA requirements. The conditions contained in both the State permit and the Federal permit constituted the RCRA Permit.

The Federal permit required the permittees to institute an Interim Measure (IM) to remediate contaminated groundwater at the PBG, and to begin an investigation of 11 areas at the facility. To date, the RCRA Facility Investigation (RFI) and the Corrective Measures Study (CMS) have been completed. The IM, installed to remediate groundwater at the PBG, has been found through additional investigation to be inadequate. This SB addresses the additional action to be taken at the PBG which is designed to intercept the plume of contaminated groundwater emanating from the PBG at the facility boundary.

In April 1993, the RI was completed for Badger. It identified the types, concentrations, and locations of contamination at the installation. The Feasibility Study (FS), completed in August 1994, looked at the possible ways to treat the contamination identified in the RI and recommended remedies for each site. The regulators agreed with the Army’s recommendations for remedies. These have been incorporated into the In-Field Conditions Report modifications of June 1995 and the RCRA permit modification of January 6, 1996, the equivalent of a CERCLA Record of Decision (ROD).

Base Closure

On November 6, 1997, Badger Army Ammunition Plant, along with four other inactive plants nationwide, was recommended for closure by the U.S. Army Industrial Operations Command (IOC) based in Rock Island, Illinois. The Army is preparing preliminary reports about the plant for submission to the Secretary of Defense of the Army, taking the Badger plant one step closer to actual closure.

In addition to the Badger plant, a recent assessment of peacetime and replenishment requirements also identified the Indiana, a portion of Kansas, Sunflower, and Volunteer Army Ammunition Plants to be excessed because they are no longer needed for current or future production. The IOC reports it will retain only 6 of its 14 inactive ammunition plants. The Command will retain Louisiana, Mississippi, Riverbank, and Scranton Army Ammunition Plants for its replenishment mission. In addition, the Command will continue to use a portion of Ohio’s Ravenna plant for storage and transfer approximately 75% of the plant to the National Guard Bureau; a portion of the Twin Cities Army Ammunition Plant will also be retained for production and a portion will be transferred to the National Guard and Army Reserve.

The announcement to excess Badger comes on the heels of a recently released GAO report which also recommended Badger for closure. Of the 14 inactive ammunition plants across the country, Badger continues to be the most expensive to maintain, costing in excess of $5 million in FY 96 alone. By comparison, the majority of the Army’s ammunition plants cost less than $1 million per year for operations and maintenance costs.

Biological Resources

A 1993 Biological Inventory of Sauk County’s Badger Army Ammunition Plant identified 16 remnants of natural communities including prairie, oak savanna, dry forest, southern hardwood swamp, pine relict, acid bedrock glade, and sandy meadow. 598 plant species were identified including 10 rare species. 47 species of birds were observed on the 7,354 acres site including a large number of grasslands birds of special concern in Wisconsin. 25 species of butterflies, 137 aquatic insects including 6 new county records and the range extension of a boreal species, 15 mammals, and 16 herptiles were identified on the Badger plant property.

The Badger biological inventory was the result of a nationwide agreement between the Nature Conservancy and the Department of Defense. The Conservancy’s work was financed by a $45,000 allocation from the federal Legacy Resource Management Program and was designed to promote the management and restoration of biological and cultural resources of Defense Department lands.

Many of the species identified at the Badger plant are found in places with such unlikely names as the Rocket Area, the Magazine area, the Acid area, the Propellant Burning grounds, the nitroglycerine pond and the Cannon range. Most of these plant and animal species occupied the prairie long before the Badger plant was built in 1942.

A major discovery of the survey was the federally threatened prairie bush clover. The bush clover and purple milkweed, Wisconsin endangered species, and at least six threatened species including the slender bush clover, the drooping sedge, the wild quinine and round-stemmed false foxglove were found at Badger.

Not surprisingly, most of the nesting birds were found in areas that are lightly grazed and see very little human activity. The diversity and variety of ponds within the plant – including old farm ponds and glacial remnant kettle ponds – support aquatic diversity ‘never found before’ in Sauk County. Among the species found, a boreal aquatic beetle previously found in only four northern counties.

Unfortunately, the purpose of the inventory was not to develop a management plan but simply to identify the natural resources within the facility. Without a management and preservation plan, the future of these natural resources remains uncertain.

Bird Inventories

Amid the hundreds of abandoned production buildings at the silent Badger Army Ammunition Plant (BAAP), singing in tall bending grasses, and nestled in pastures dotted with grazing cattle, scientists have found a rich variety of grassland birds and habitat that may play a critical role in wildlife conservation and efforts to protect the Nation’s migratory birds.

Preliminary results of a recent volunteer biological inventory, coordinated by the Aldo Leopold Chapter of the Society for Conservation Biology, found 28 species of birds, plants and mammals of conservation concern at BAAP. Among the most remarkable results were the bird surveys. Of the migratory birds undergoing the most serious declines, grassland birds have undergone many of the steepest declines, those are exactly the birds found to be particularly abundant at Badger.

Throughout the United States, many migratory birds are undergoing serious declines in their numbers. Birds using grasslands have declined more than birds using either forest or scrub habitats. In fact, two-thirds of the species of American grassland birds are declining.

The 1998 spring and summer surveys at BAAP found 16 species of birds of conservation concern at BAAP. Of these 16 species, 15 are listed by the State of Wisconsin as being Endangered (Peregrine Falcon), Threatened (Henslow’s Sparrow and Osprey), or Special Concern (Bobolink, Grasshopper Sparrow, Red-headed Woodpecker, Field Sparrow, Eastern Meadowlark, Vesper Sparrow, Western Kingbird, Western Meadowlark, Upland Sandpiper, Cooper’s Hawk, Dickcissel and Orchard Oriole.) One Watch List species, Clay-colored Sparrow, was also found at BAAP.

Although biologists have found grassland birds among the scattered inactive buildings, poles, and pipelines, they believe the potential for improving species numbers and habitat could be markedly improved by the removal of buildings.

Some birds, such as Upland Sandpiper, require more acreage than other species. Consequently, building removal would benefit species requiring larger area requirements and yet not likely harm species with small area requirements. Furthermore, expanding existing grasslands might attract birds with even larger needs, such as Northern Harriers, and Short-Eared Owls, that are now missing from BAAP.

Grassland birds of conservation concern were found throughout much of BAAP. In particular, all of these grassland birds were found in the western one-third of the plant, the area with the greatest concentration of buildings. The grazed areas in the western and central portions of the plant had more grassland birds than did the areas the Army manages for wildlife adjacent to Devil’s Lake State Park or those under row-crop agriculture.

Another factor in the apparent success of bird species at BAAP is the remarkable size of this property. Badger’s 7,354 acres provides a variety of habitats which in turn have attracted a wide range of species. Some grassland birds, such as Upland Sandpiper, require short grass habitat. Others, such as Bobolink and Henslow’s Sparrow, require habitat with taller grasses. Sufficient acreage for both short and tall grass habitat, providing an environment with such a rich variety of species, is found in few places in the Midwest simply because most other properties are too small in this regard.

Maps, using a Geographic Information System (GIS), are being prepared of the locations of the various plants, animals, and other organisms at BAAP. The work on the maps began in October and given the importance of the bird data, they were mapped first. A final analysis of the inventory data is forthcoming.

Clearly, BAAP is critically important in maintaining, and possibly recovering, some of the biological richness of Sauk County’s disappearing native grasslands. BAAP plays a crucial role in protecting Sauk County’s natural heritage. That role can change, for better or worse, as BAAP’s future is decided.

Ho-Chunk Nation

Through the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Ho-Chunk Nation has made a formal request to the General Services Administration (GSA) that approximately 3050 acres of property at the Badger Army Ammunition Plant transferred in trust for the benefit of the Nation. The BAAP land has very important historic and cultural significance to the Ho-Chunk people. The land lies within the heart of Ho-Chunk’s aboriginal territory, including villages located within present-day Sauk County, and in particular, along the Wisconsin River, where the Badger Army Ammunition Plant is located.

The Nation’s primary interests are: (1) the protection of the cultural, historic, archeological and natural resources located on the property, (2) the restoration of prairie, native plants and animals, (3) the restoration, remediation and continued protection of the environment, both the human environment and the natural ecological environment. The preservation of the history of the Ho-Chunk Nation and successor communities of the great Sauk Prairie Land is fundamentally important. It preserves the past while preparing the future.

Land is permanent and stable, a source of spiritual origins and sustaining belief. Land is an important social institution, one intimately connected to the environment, resource management, heritage preservation and economic development. Through community operation and integrated land use planning, it is possible to preserve, conserve and protect the Natural Resources of this State. It is possible through a collaborative effort, joint support and mutual assistance to restore the Sauk Prairie. The efforts of community, farmers, environmentalists, sports-persons, conservation groups, historians and local and tribal government, the restoration, remediation and protection of the environment, history, and cultural resources can be achieved.

The Ho-Chunk Nation’s goals and objectives are consistent with the uses envisioned at the former Badger Army Ammunition Plant. The goals of this community are achieved with the involvement, cooperation and resources of all interested parties. The land use is the key to this equation. Ho-Chunk, like the voices of the public and WDNR, has stated that its desired use and objectives are to aid in cleaning-up the environment, ensuring a clean green space for people and wildlife. Eco-tourism, restoration of prairie, habitat and wildlife, and the preservation and protection of traditional cultural properties are invaluable to the history of this land and its people. The protection of and preservation of earthwork, mounds, cultural sites, including the re-establishing native plant and animals like Bison, as a native species to the prairie, are essential to the revitalization of Ho-Chunk traditional practices and culture. These desired objectives are consistent with the prairie restoration desired by the area people. It does not conflict with, but compliments the land use practices of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and surrounding neighbors.

The Ho-Chunk Nation is committed to protect and enhance natural resources. The Ho-Chunk Nation has undertaken a prairie restoration and bison project to enhance the traditional beliefs of the Tribe. The Nation operates resource management programs to “acquire, manage, develop and enhance tribal resources” including “land, water, fish and wildlife, range, forestry, irrigation, and other programs designed to manage, develop and enhance tribal resources.” The BAAP facility is located on lands that historically were prairie and woodlands. Since the 1960’s, portions of the BAAP lands have been the subjects of wildlife restoration projects. The Nation wishes to expand its prairie and bison projects. The Nation’s proposed use of the property is consistent with the interests expressed by many members of the local communities and environmental groups, and would benefit those communities. For all of these reasons, the Ho-Chunk Nation has requested that the Department of the Interior seek to acquire the BAAP in trust for the benefit of the Nation.

State and Federal Agencies

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) has expressed interest in owning and managing all of Badger’s 7,354 acres. The DNR has forwarded its request to the Wisconsin Department of Administration (DOA). If the DOA agrees with the DNR’s plan, the request will go to the Governor for his approval. However, these steps don’t guarantee DNR ownership of Badger.

Already at a federal level, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has requested the use of land for the Dairy Forage Research Center, and the Department of the Interior has requested the use of land for the Ho-Chunk Nation. Under the General Services Administration (GSA) process for disposal of excess federal properties, these two federal agencies will have first choice of land, followed by the state. All interested agencies will have to prove they have a use for the land.

Under the Federal Lands to Parks program, the DNR is eligible for transfer of these lands at no cost if they will be used for public park and recreation purposes. Under this program, properties must be used for public park and recreation purposes in perpetuity, including protecting and providing pubic access to natural and historic areas such as lakes, rivers, forests, wetlands, open space, shorelines, and historic buildings.

According to Wisconsin law, state aids will be paid to local government with respect to these lands. These state aids will be roughly equivalent to property taxes that would be levied on land acquired by the DNR if the land was subject to property taxation. Revenue from the sale, recycling, and salvage of surplus equipment and other accounts at Badger will help pay for environmental cleanup, estimated to cost as much as $250 million.

The DNR envisions managing the property as a multi-use facility primarily for ecological restoration and maintenance of prairie and oak savanna. Proposed uses include hiking, biking, cross-country skiing, nature appreciation, hunting, educational opportunities, cultural awareness opportunities, and more. Contiguous wildlife conservation lands at Badger would function as a protected buffer area for Devil’s Lake State Park, provide connectivity of habitats between Devil’s Lake State Park, the Baraboo Hills, and the Wisconsin River, and reduce habitat fragmentation.